OSMP Collection

Shahed-131 & -136 UAVs: a visual guide

This is the second in a series of articles using interactive 3D models to explain widely used munitions to a general audience. The model below highlights key parts of the Shahed-131 and Shahed-136 UAVs alongside component descriptions and relevant entries from the OSMP munition archive. You can also read this page in Ukrainian here. The first article, on the American-made GBU-39, can be viewed here.

The Shahed-131 and Shahed-136 are one-way-attack (OWA) unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), often called ‘kamikaze drones’ or ‘suicide drones’ in the media. Whilst derived from UAVs, these munitions are essentially guided missiles — flying towards pre-designated targets and exploding on impact. The Shahed series are originally of Iranian design and were first documented in use with Iranian and Iranian-backed forces in the Middle East.

Following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia began to receive shipments of these drones from Iran, designating them the ‘Geran-1’ (Shahed-131) and ‘Geran-2’ (Shahed-136). Russia then reportedly received permission to begin domestic mass production of the munitions with Iranian assistance. Each Shahed is reported to have an estimated cost between $20,000 and $50,000, making them cheaper than most other long-range, OWA UAVs. This low cost, along with a low-altitude flight profile and self-sacrificial nature has seen Shaheds labelled “the poor man’s cruise missile”.

Comparison of Shahed-131 and 136 UAVs

This interactive displays models of the Shahed-131 and Shahed-136, allowing you to compare key visual features and learn about similarities and differences in design.

Click on a button below to view the key component parts of the munitions. Each part is accompanied by technical details and presented alongside images from the OSMP archive.

Shahed-131: Length of 2.6 metres, wingspan of 2.2 metres.

Shahed-136: Length of 3.5 metres, wingspan of 2.5 metres.

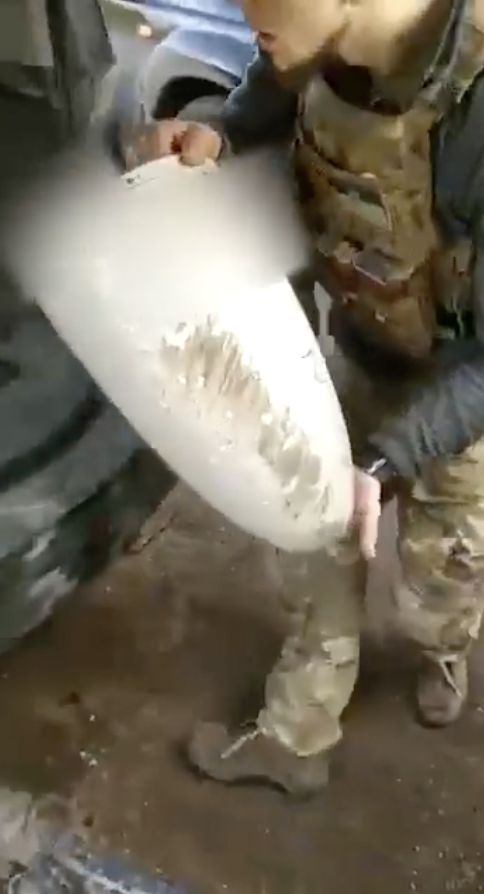

The nose cone, which acts as an aerodynamic cover, is found at the front of the munition and is located forward of the warhead.

Shahed munitions utilise a range of warhead variants, including original Iranian-designed high explosive fragmentation warheads and shaped charge warheads, as well Russian-designed high explosive fragmentation, shaped charge, and thermobaric warheads.

Shahed-131: A 10 to 20 kg warhead is located near the front of the munition.

Shahed-136: A 50 kg warhead is located near the front of the munition, although later Russian-produced variants may contain warheads weighing up to 90 kg that extend further back into the munition.

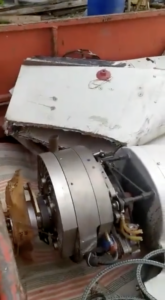

Two delta (triangular) wings extend from the central fuselage. These are made from fibreglass, and may incorporate carbon fibre on Russian-designed variants. Shaheds often contain a honeycomb structure, which aims to reduce the munition’s radar cross section, decreasing an adversary’s ability to detect the munition during flight.

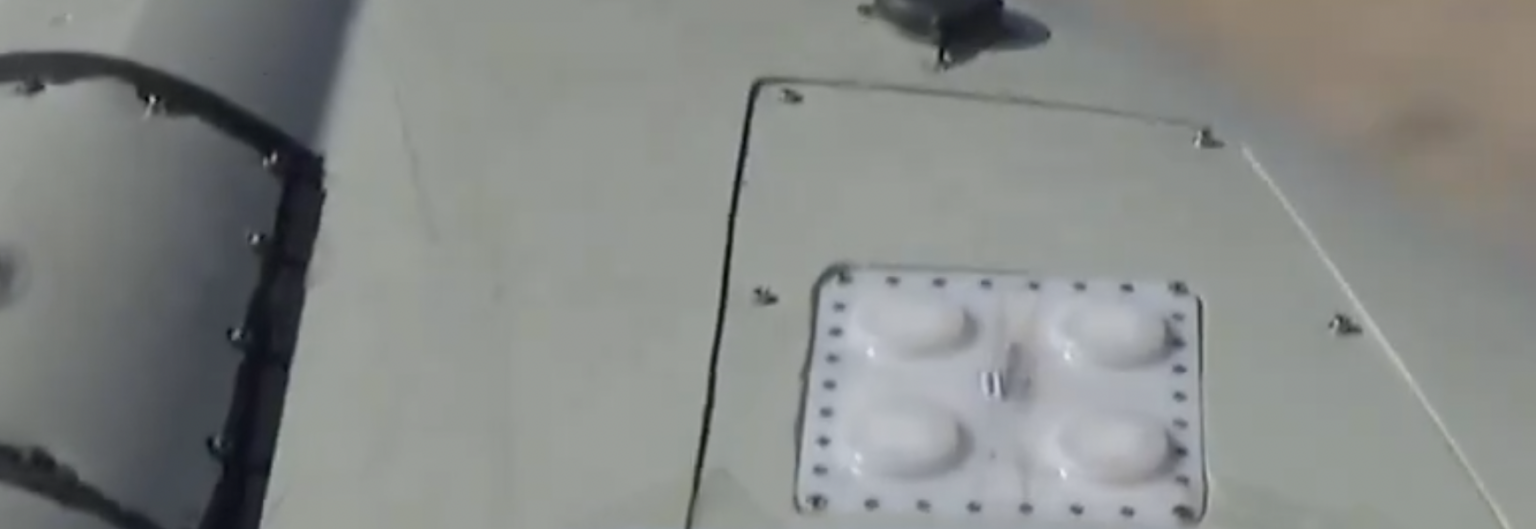

Shahed-131/136 UAVs cannot be remotely piloted. Instead, they use Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), such as GLONASS or GPS, to fly towards and strike pre-programmed target coordinates. A white-coloured, four-puck GNSS antenna assembly is typically visible on the right-hand wing of the munition.

The vertical wing stabilisers are located at either end of the wings and provide additional control, while ensuring the munition maintains stability.

Shahed-131: Stabilisers only extend above the delta wing assembly.

Shahed-136: Stabilisers extend both above and below the delta wing assembly.

Four fins are located at the rear of the munition, with two fins per wing. These control surfaces are connected to the main body by hinges and are adjusted by onboard systems to alter the munition’s trajectory during flight.

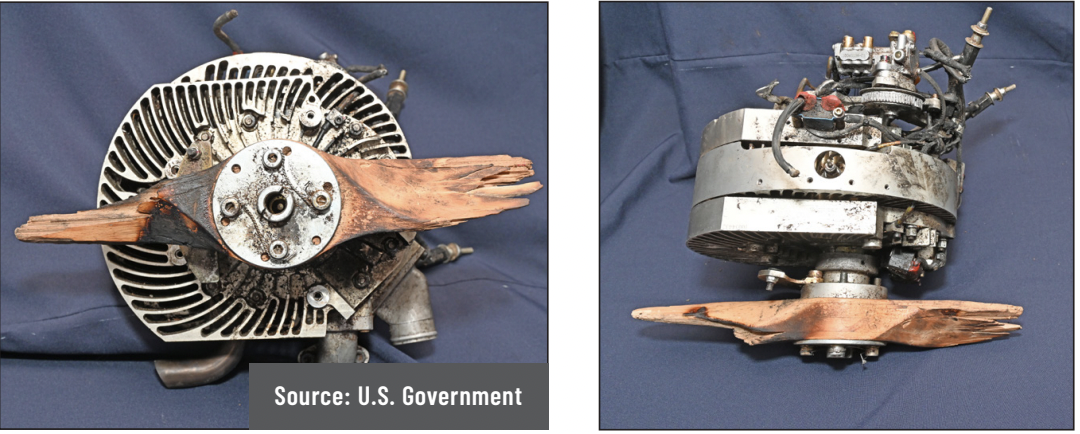

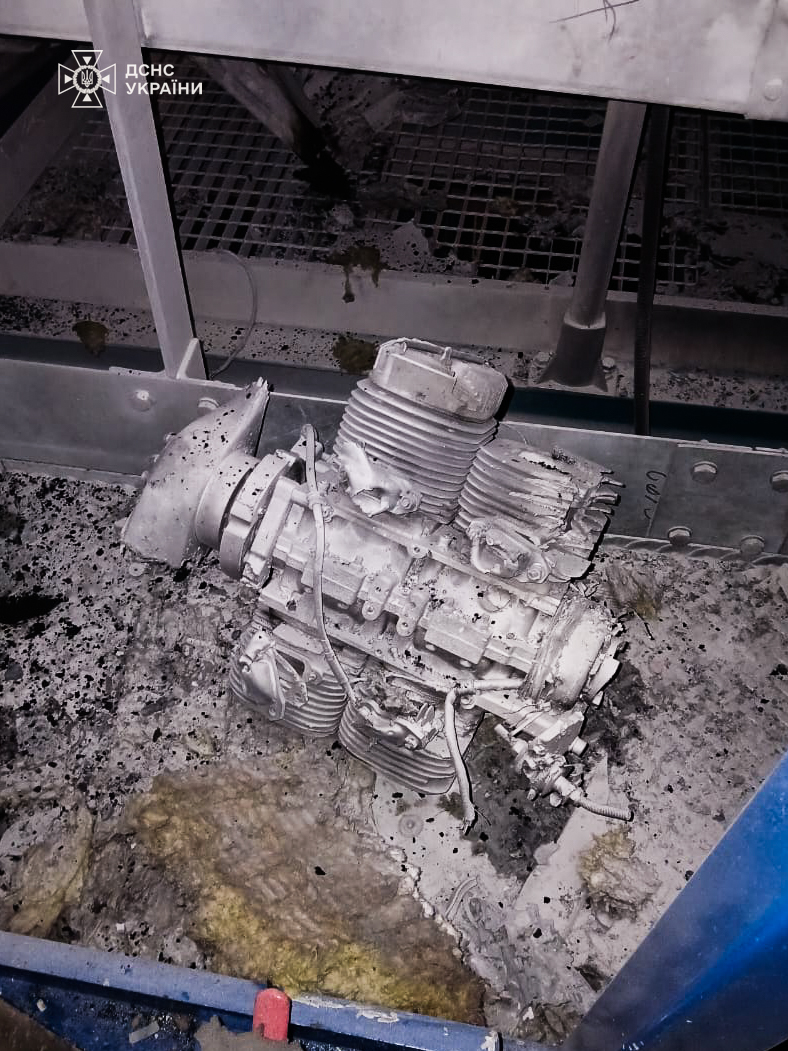

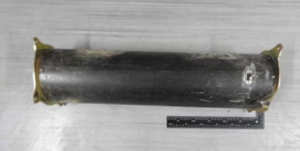

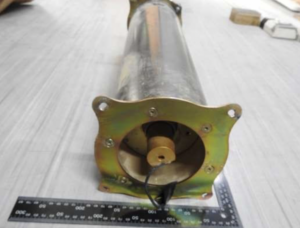

A single-propeller piston engine can be found at the rear of the munition, providing propulsion to drive the munition forward towards its target.

Shahed-131: A smaller MDR 208 variant motor is employed, which provides a maximum effective range of at least 700–900 km.

Shahed-136: A larger MD-550 variant motor is employed, which provides a maximum effective range of at least 2,000 km.

Low cost, mass attack

Shahed-131/136 munitions—Shahed meaning ‘Witness’ in Farsi—are a family of OWA UAVs originally designed and manufactured by Shahed Aviation Industries, an Iranian aerospace company. The Shahed-131 is a smaller munition with a range of 700–900 km, while the larger Shahed-136 has a range of at least 2,000 km. The munitions are precision-guided, flying along manually-inputted geocoordinates before diving onto their targets and exploding. Investigations into the drones’ technical components found a variety of western-made commercial technology used in their assembly.

Shahed UAVs, like other OWA UAVs, are classified as missiles as they fit the definition of “a powered munition with the ability to alter its trajectory once it has been launched”. As a result, OWA UAVs such as the Shahed series, are categorised as a ‘Rocket or Missile’ and ‘Guided Munition’ in the Open Source Munitions Portal. OWA UAVs are also given the additional domain tag ‘Drone (UAV)’ for accessibility.

Shahed-series munitions are launched using a disposable rocket-booster fitted to their underside. Shortly after launch, the booster is jettisoned and a piston-driven engine takes over to provide propulsion. Their relatively slow speed and the loud hum of their engines has led to Shaheds being called “flying mopeds” by Ukrainians living under their flightpath. Shahed munitions may be launched from both static rail mounts as well as vehicles, with one video published by Iranian media showcasing five Shahed-136 munitions being launched from a truck’s cargo hold.

The first confirmed use of a Shahed-series munition—specifically the Shahed-131—was during a series of attacks on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq and Khurais oil facilities in September of 2019. These attacks, attributed to Iran, involved nearly two dozen munitions flying in close formation and performing sequenced strikes on infrastructure at the Abqaiq oil facility, causing extensive damage.

Iran also provided these munitions to a variety of allied non-state actors across the Middle East, including the Houthis in Yemen and the Islamic Resistance in Iraq.

Following the 24 February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russia began using Shahed-series munitions to perform strikes on key energy infrastructure, as well as railways, residential buildings, and vehicles across the country. As of 2025, Russia dramatically increased the frequency of attacks in an attempt to overwhelm Ukrainian defences, with an average of 140 Shaheds recorded every day in February.

The use of advanced air defences to defend against these threats has remained a pressing issue, with the cost of sophisticated interceptors generally far greater than the price of the Shaheds themselves. This issue was exemplified during Iran’s April 14th attack on Israel—dubbed Operation True Promise—which involved hundreds of munitions, including Shaheds, being launched in waves. During the attack, the RAF was reported to have employed ASRAAM air-to-air missiles—which have an estimated cost of $225,000 per unit—to shoot down much cheaper Shaheds, which have an estimated cost of just $20,000–50,000.

Ukraine was also reported to be using the same British-supplied missiles, modified for a surface-to-air role, to shoot down Shaheds fired from Russia. Cheaper air defence methods have also been employed, including shooting down Shaheds from helicopters or trucks using machine guns, and cheaper surface-to-air missile systems, such as the VAMPIRE system that fires AGR-20 APKWS II missiles at a cost of $27,500 each. AGR-20 APKWS II missiles have also been fired from U.S. jets to down Houthi missiles. Other UAV countermeasures are under development, including the use of electronic warfare and domestically manufactured interceptor drones.

A large group of Shahed drones fly over Ukraine, Oct. 19th, 2024. (@Archer83Able)

Since their first use by Russia, there has been evidence of significant adaptations beyond Iran’s initial design.

A constantly evolving munition

Following initial shipments of Shahed munitions from Iran, Russia established domestic production facilities for the creation and development of their own variants of these munitions at the Alabuga Special Economic Zone. The facility expanded over time as the production rate of Shaheds increased, and aimed to produce 6,000 units in 2024. Since their first use by Russia, there has been evidence of significant adaptations beyond Iran’s initial design.

Firstly, changes have been made to make the munition harder to detect. The original white base colour of the munitions has been replaced with a matte black design, reportedly in order to make them harder to spot at night. Shahed-136 munitions used by both Iran and Russia have also been documented using a honeycomb structure inside their wings—probably to reduce the likelihood of detection by radar.

Secondly, Russia has adapted the munitions to skirt evolving Ukrainian countermeasures. Due to Ukraine’s increased use of electronic warfare, (EW) or ‘spoofing,’ Russia has reportedly added new Chinese antennas to their drones, which allow for greater protection against such interference. Other types of CRPA (controlled reception pattern antenna), originally designed for agricultural use, have also been found in the drones, either to minimise production cost, or due to the antennas’ eight-figure configuration facilitating greater EW resistance.

Thirdly, Russia has produced its own warheads for the Shahed-136, with a number of new variants listed in leaked documents from the Alabuga production site—some of which have been documented in use in Ukraine. These include the BSF-50, a 50 kg warhead which combines high explosive, fragmentation, and incendiary effects, as well as the TBBCh-50M, which contains a thermobaric explosive composition and also incorporates a fragmentation effect. One of the largest documented Russian warheads for the Shahed-136 is the BCh-90, a 90 kg shaped charge warhead with an additional fragmentation effect. The leaked documents call for the BCh-90 warhead to be constructed with a composite fragmentation liner of steel and zirconium, a metal used to generate both fragmentation and incendiary effects. Whilst more powerful than the standard 50 kg design, integrating the larger 90 kg warhead requires switching to a smaller fuel tank on the munition—leading to a significantly decreased range.

Iran has also reportedly developed a range of different warhead designs for the Shahed series. Shahed-131 munitions, for example, have been found to use multipurpose warheads which employ a shaped charge warhead surrounded by 18 small discs around the warhead for an additional anti-armour effect, as well as a crudely implemented fragmentation liner consisting of metal cubes to generate an additional fragmentation effect. The Iranian Shahed-136 has also been documented with a reinforced steel casing in its nose cone to provide a limited penetrating capability against hardened targets.

Alongside serial production of the Geran-1 and Geran-2, Russia also reportedly developed its own version of the Shahed in 2023, the Garpiya-A1. The Garpiya is claimed to have a range of up to 1,500 km and is produced by a subsidiary company of Russian weapons manufacturer Almaz-Antey. The munition reportedly uses a large number of Chinese-made components, including a Chinese version of the Iranian-made MD-550 engine. The Garpiya-A1 has reportedly not been widely used in Ukraine.

Finally, an entirely new variant of the Shahed-136 family has emerged—seemingly in use by both Iran and Russia. Known as the Shahed-238, this munition reportedly uses a turbojet engine rather than standard piston engine to propel the aircraft forward. This modification dramatically increases the munition’s speed, potentially making it harder to intercept while also shortening the time between launch and impact. An analysis of wreckage found in Ukraine identified the turbojet as the TJ150—a Czech-made engine—reportedly providing the munition with a cruising speed of around 520 km/h, far more than the reported 180 km/h of the standard Shahed-136. In February 2025, Ukraine’s Defence Intelligence claimed Russia had begun establishing a domestic production line for the Shahed-238, which Ukrainian reports referred to as the ‘Geran-3’.

It (a Shahed) crawled literally over our roof - a huge lawn mower sound overhead. It was very, very loud. We followed the sound that passed our house, and then after that we shrank because we realised that there was going to be an explosion.

Civilian impact

Although the Shahed-131 and Shahed-136 are precision-guided munitions, their use has heralded devastating consequences for civilians and civilian infrastructure across Ukraine. On 30 January 2025, for example, a Shahed struck a residential building in the city of Sumy, destroying five apartments across four floors and killing at least nine people, with 13 others reported injured. A separate strike on 23 March 2025 in the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, hit another set of apartment buildings, killing at least three civilians. Just seven days later, a group of 20 Shahed munitions struck in Dnipro, leading to the deaths of four.

Marcel Plichta, a fellow at the Centre for Global Law and Governance at the University of St Andrews and a former analyst at the U.S. Department of Defense, explained Russia’s Shahed drone tactics in an interview with Airwars: “Shaheds have mostly been used for strategic, almost terror bombings, behind the front lines, taking advantage of their long range to attack major cities. The Shaheds let the Russians keep up the tempo and the pressure of the operation.”

Beyond the physical danger posed by Shahed UAVs, the sustained use of such munitions has also had profound psychological effects on Ukraine’s civilian population. This is largely due to the loud humming noise of the munitions’ propeller engines, with some likening their sound to that of the infamous V-1 ‘flying bombs’ of the Second World War. An AP report highlighted how the “incessant buzzing” of the motor “can only exacerbate the anxiety and chip away at the morale of any person not knowing exactly when and exactly where the weapon will strike”.

A Shahed OWA UAV strikes a residential neighbourhood in Kyiv, Ukraine, Feb. 20th, 2025. (@markito0171)

External Resources

Royal United Services Institute – Russia’s Iranian-Made UAVs: A Technical Profile

Janes – Ukraine conflict: Details of Iranian attack UAV released

Conflict Armament Research – Documenting the domestic Russian variant of the Shahed UAV

Conflict Armament Research – Multipurpose Iranian drone warheads used in Ukraine